I didn’t mean to write a mummer’s play. They say you should write about what you know, and I didn’t know very much about mumming, not at first.

I’ve been a morris dancer for many years. Almost ten years ago, for a creative writing challenge, I started by writing a three act play about the rivalry between fictional morris dance sides. The play would include various types of events that morris dance sides are often involved with. The middle act would be based around a mummer’s play that one of the morris sides would perform. As the story was set in Bristol, I decided that the mummers play would be about a local hero and my first choice was the civil engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

By the time I’d finished writing the middle act, it was obvious that this was the part of the story that I’d expended all my energy on and the rest was quickly forgotten. The mummers play would take on a life of its own, not least because I was a long standing member of Rag Morris, a non-fictional morris dance side who would prove to be interested in performing that mummers play in its entirety.

When I first started, the only mummers play script I had a copy of was the last original mummers play that Rag Morris had staged in public. This was the story of Vincent and Goram, two legendary giants who were said to have carved out the Avon Gorge, a spectacular river valley next to the City of Bristol. That play was composed by local artist, author and former Rag Morris dancer Marc Vyvyan-Jones, with help from Roland and Linda Clare. Because that play was fairly loosely based on mumming play conventions, I figured that I would write my play to tell its own story with characters based on mumming archetypes and some of the structure from a mummers play, but to use the characters as storytellers to relate a series of incidents from Brunel’s biography, with bad puns, rhyming couplets and dramatic reconstructions.

The Vincent and Goram play begins with an introduction by Old Father Thyme; so I started my play by converting this speech into an introduction by Old Father Thames, a traditional folkloric representation of the English river in human form.

OLD FATHER THAMES

In comes I, Old Father Thames,

Welcome or Welcome Not

I hope Old Father Thames

Will never be forgot.

I rise in the west and flow to the east

Towards the rising sun

I began my journey before you were born

I’ll be going when you are long gone

The tale I have to tell this day

Is of a hero bold

A Great Briton they have called him

Though his story’s not that old

So come with me a century

Or two into the past

For now it’s time to step aside

And introduce the cast

In 2002 the BBC ran a poll, encouraging people to vote for the person they considered to be the Greatest Briton; and Isambard Kingdom Brunel came second, after Sir Winston Churchill.

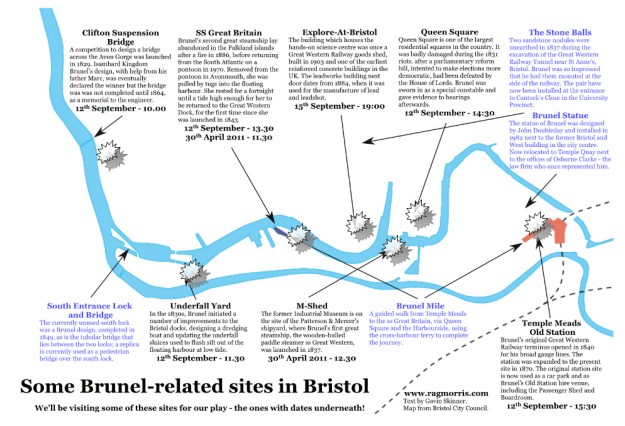

The extraordinary life of I.K.Brunel lent itself admirably to a reinterpretation in the form of a mummers play. I started writing the play a couple of years after the celebration of Brunel’s 200th birthday in 2006; an anniversary that was marked with a series of events in Bristol. An exhibition entitled “The Nine Lives of I.K.Brunel” hosted in Bristol next to his great ship, the SS Great Britain, provided both the title and structure of the play. I began to read biographies, diaries and articles about the engineer to find out as much as I could about the story and and the subjects I wanted to portray.

All the incidents described in the play are based on historical fact; with a story as rich as this, full of ambition and success, comedy, tragedy and some frankly ridiculous accidents, there was no need to make any of it up. The award-winning Horrible Histories TV series, based on a series of books, uses the same process of sticking as closely as possible to the historical truth to draw out the humour of the situations. The first series was broadcast in 2009, the same year that the Brunel Play made its debut. I don’t believe that Horrible Histories have done a full episode on Brunel yet but I’d be open to offers if they want to use any of my rhymes.

Our hero introduces himself with a straightforward couple of verses

BRUNEL

In comes I, I’m Isambard –

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

An Engineer I am by trade

With many a tale to tell

I’ll build the biggest ships

and I’ll design the fastest trains

But mostly I’ll be famous for

Smoking by giant chains.

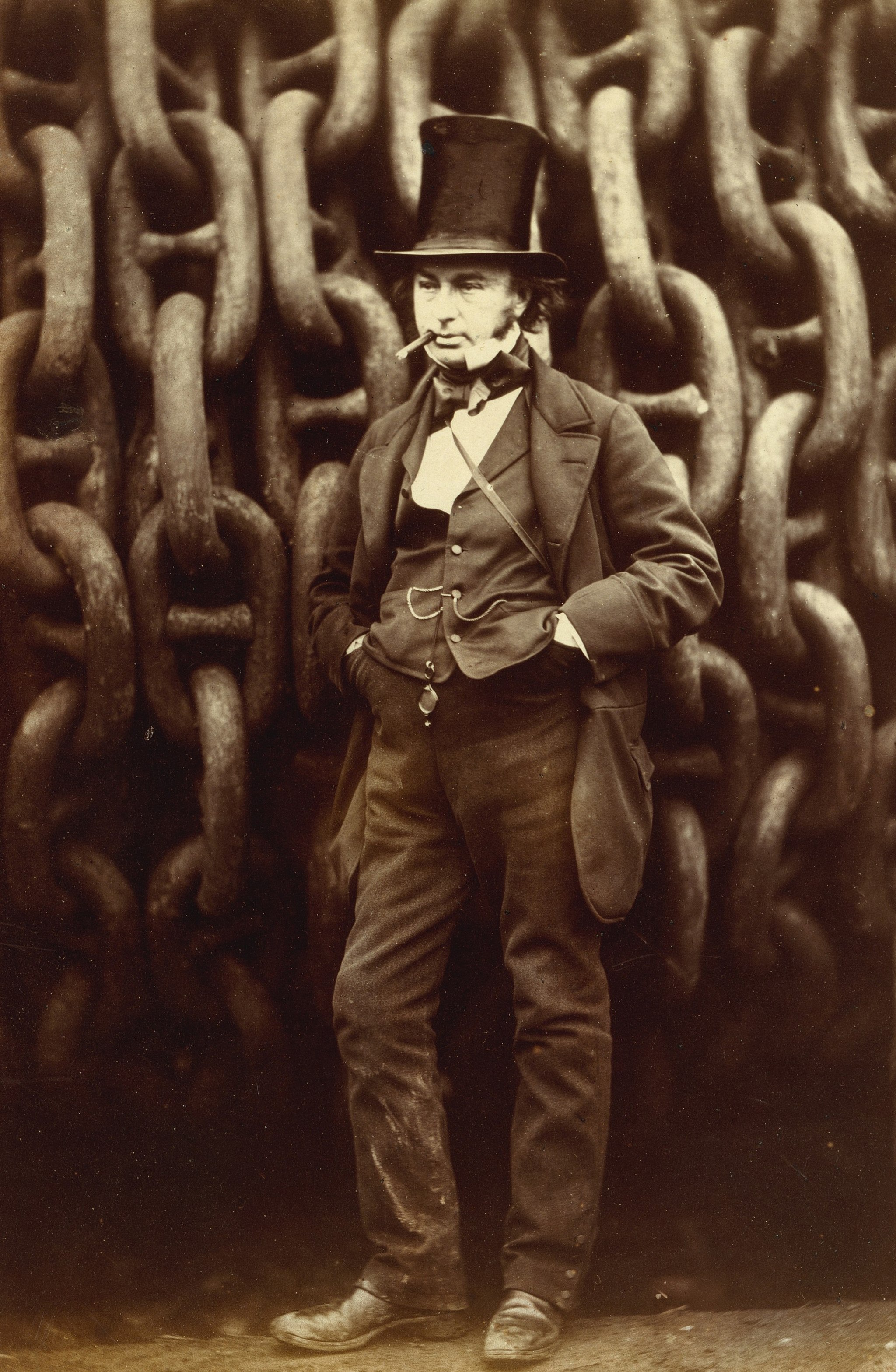

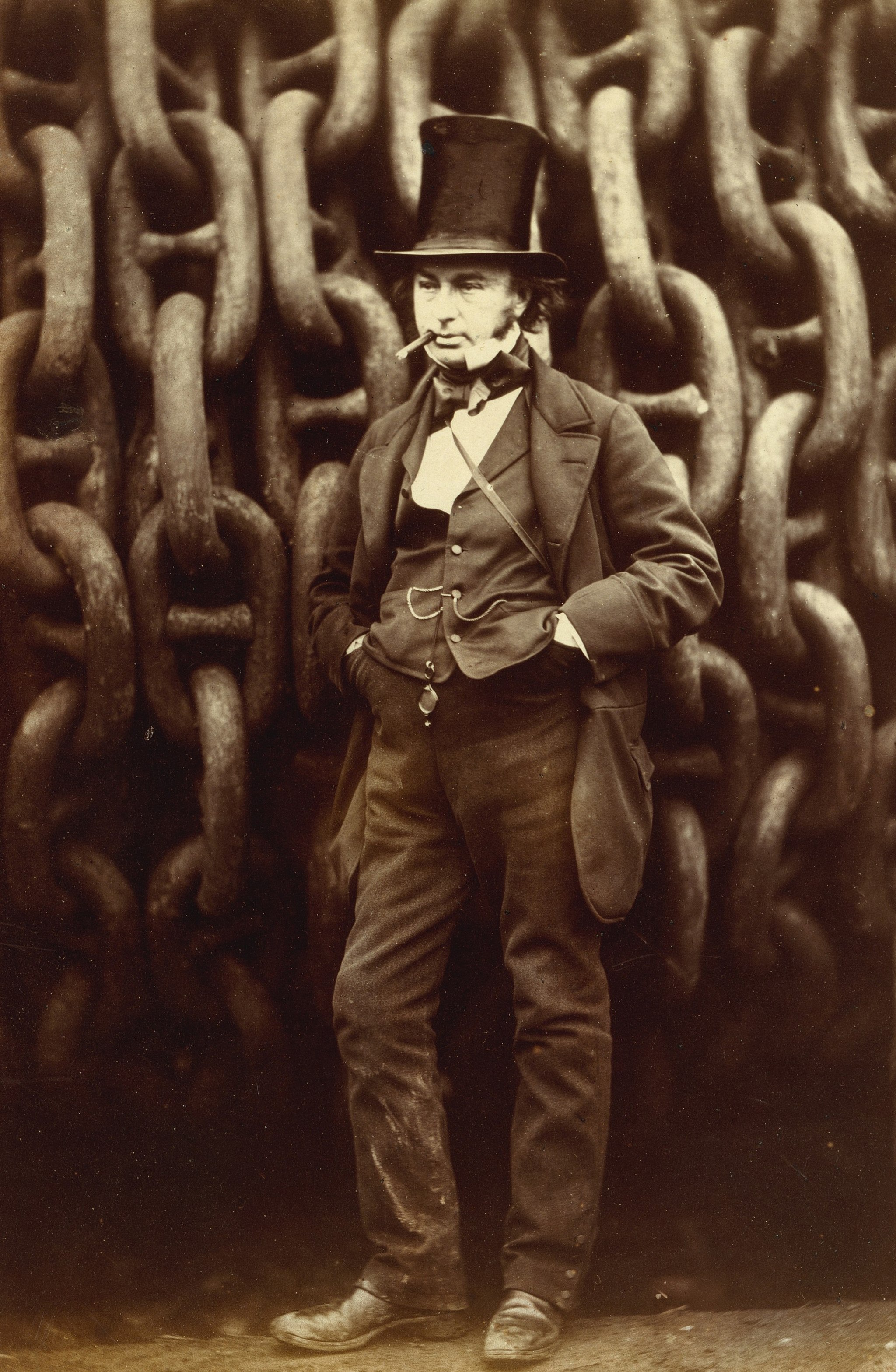

A famous photograph of Brunel, by Robert Howlett, shows him standing next to the drums which held the chains used for launching his monumental ship, the SS Great Eastern; hands in pockets, puffing on a cigar. It’s the most iconic photographic portrait of the Victorian era, and so I was keen to get in a reference to that image early on in the play.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel Standing Before the Launching Chains of the Great Eastern, photograph by Robert Howlett.

The other characters introduce themselves. Doctor Foster, down from Gloucester, is a traditional mummers play character who will help revive our hero after his numerous accidents, representing the many physicians who did so in real life.

For one example, in his later years, Brunel’s doctor was his brother-in-law and friend Seth Thompson. He was the doctor who first helped Brunel when a half-sovereign accidentally dropped into one of his lungs while performing a magic trick. He also accompanied Brunel and his family on a recuperative trip to Egypt during the last year of his life, and was an executor and beneficiary of Brunel’s will.

The Vincent and Goram play features a character called Brunel-zebub as the traditional diabolical panhandler at the end of the play. St Vincent’s rocks on the Avon Gorge was eventually the site of Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge, Brunel’s first great undertaking, eventually completed as a memorial to him to become an icon for the City of Bristol. In my play Brunelzebub is the villain of the piece, whose ambition is to thwart Brunel’s plans and remind him of the rising death toll that accompanied his ambitious projects. He forms a double act along with Bold Slasher to represent Brunel’s inner demons or ‘Blue Devils’ that he described in his diary during his periods of self-doubt.

Then in comes Little Johnny Jack, with his family on his back. In our play, this character, along with Old Father Thames, provide the exposition, helping to set the scene for each of the nine episodes.

With these characters in place I then began to translate each of the stories into verse and rhyme, each of the episodes lasting couple of minutes at most. I was constrained by the facts that I wanted to fit in to each segment; I wrote at the top of the script, “Abridged by Gavin Skinner”, as it felt like I was creating a rhyming summary of an existing story; and in Bristol, Brunel himself was well known building a bridge.

At the time I was writing the play, my eldest was three years of age, so I was reading a lot of children’s story books. Writers who specialise in this field such as Dr Seuss, Julia Donaldson and Lynley Dodd have probably written more poetry that is actually read out loud than anyone else, and I’m sure my familiarity with their work at that time made it easier to pick and choose rhymes and rhythms.

Here are a few examples of some of my favourite lines from the play, with an explanation of some of the source material and ideas which went into the composition.

I was keen to write a bridging verse between each of the stories and was looking for a connection between the elegant Queen Square, where Brunel fought as a special constable as it was ruined during Bristol’s riots in 1831, and the story of his Great Western Railway. I found my answer in a magazine article that referred to a little-known fact from Brunel’s diary; at one time he considered siting his railway terminus in the square.

BRUNEL

This riotous conflagration’s left Queen Square in devastation

Making it a prime location for the station Bristol needs

But should the City’s Corporation recommend its restoration

I’ll build my station by the Avon in a field called Temple Meads

After an episode in which Brunel fails to listen to expert advice during the delivery of a railway locomotive, it’s up to Little Johnny Jack to link to the next topic.

JOHNNY JACK

The Great Western Railway became a success

But what to do next made Brunel rather frantic

He wanted the journey to go further west

By Great Western Steamship across the Atlantic

BRUNEL

The problem is this – there are those who insist

That an Atlantic steamship just cannot exist

That a big enough hull would require so much coal

You would always run out before reaching your goal

But I’ve done some sums that just prove that they’re wrong

And that nautically I’m engineer number one

My ship will go fast and will be built to last

And have room for the passengers too – that’s first class

Johnny Jack links neatly from one story to the next. Brunel’s speech, with a slightly different rhyming structure, is meant to reflect the rhythm of the steam engines that drive the ship. An earlier version of the speech included a rhyme with “boat” and “float”, but I was told unequivocally by a representative of the SS Great Britain that Brunel built ships not boats.

The verses allude to the long-running dispute between Brunel and Victorian author and science communicator Professor Dionysius Lardner, who insisted that as a ship’s size increased, so would its requirement to store coal; meaning that no ship could be big enough to travel by steam over the Atlantic. Brunel proved that the fuel carrying capacity of a ship is related to the cube of its size whereas the drag of the hull, which dictated the power required to drive the ship, is in proportion to the square of its size; which meant it was perfectly possible for his large steamship to cross from Bristol to New York with coal to spare.

The story of the Battle of Mickleton Tunnel is one of the most astonishing and yet little-known episodes in Brunel’s industrious career. The contractors hired to dig a railway tunnel in Gloucestershire believed they were owed money by the railway company and downed tools and prevented the railway company from accessing the tunnel. In an utter breakdown of employment relations, Brunel raised an army of three thousand navvies from other projects in order to take back control, by force.

OLD FATHER THAMES

The fighting began, several heads and limbs broken,

Some shoulders popped out and one skull cleft in two

with a shovel; but no-one killed outright, so that’s alright,

and victory to the company in the morning dew!

The contractors found that resistance was futile

And the contract redrawn over cups of hot tea

Brunel’s private army the last to have fought

A pitched battle on the soil of our fair country

The description of the fight was almost word for word from one of the accounts of the battle.

The last of the Nine Lives, and the final character to appear, concerns Old Leviathan, the nickname for the Great Eastern, the largest ship ever built when she was launched in 1858; a record that would be held until she was broken up just over 30 years later.

OLD LEVIATHAN

In comes I, old Leviathan

Brunel’s greatest project

And his last

They said that I killed him

I almost quite ruined him

The world’s finest ship

I’ve come back from the past

So why did he build such a monstrous Leviathan?

To travel non-stop to Australia by steam!

No ship will surpass me for half a man’s lifetime

There’s no power on Earth that can compare with me

The last line was inspired by the cover image from Thomas Hobbes’ book, “Leviathan”, that I spotted in a newspaper while writing the play. This includes the inscription, “Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comperatur ei”, itself a biblical quote from Job chapter 41: “There is no power on earth to be compared to him”

But the stress of building the monstrous ship was too much, even for Brunel; he visited his marvellous ship for the last time shortly before her maiden voyage, when he suffered a stroke.

In our play, this represents the final victory for the blue devil Brunelzebub, who in a final act of indignity, recounts Brunel’s last days in the form of a limerick; albeit one with a deliberate break in the rhythm or scansion in the second line.

BRUNELZEBUB

As Brunel he went home and was lying on

His deathbed…

…his steamship was flying on

Then some pipes overloaded,

A boiler exploded

And six stokers were dying on Leviath-on

Brunel built his great reputation

On the work of the men of this nation

Only some paid the price

Of their own sacrifice

What they need is a standing ovation

This character represents the engineer’s inner demon, and it seemed appropriate to give voice to his own regrets and self doubt at this point. Brunel’s son Isambard wrote of his father in his biography, “The Life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Civil Engineer”,

In times of difficulty, such as the trial of the Atmospheric System and the launch of the ‘Great Eastern’, his chief thoughts were for those who would suffer through the failure of his plans.

Each of the characters then stands to give their own tribute to Brunel, or in the case of Bold Slasher, something based on a less than flattering obituary:

Not one of the great schemes which he set on foot can fairly be called profitable, and yet they are cited, not only with pride, but with satisfaction, by the great body of a nation supposed to be pre-eminently fond of profit; and the man himself was, above all other projectors, a favourite with those very shareholders whose pockets he so unceasingly continued to empty.

There is always something not displeasing to the British temperament in a magnificent disappointment.

Obituary in the Morning Chronicle 1859

This translated into rhyme like this:

BOLD SLASHER

This ambitious, reckless engineer

Financially so cavalier

His work cost his investors dear

As profits tumbled year on year

Which they accepted with good cheer

Good grace and no resentment

His shareholders would never fear

For he would always “pioneer”

With bold abandon persevere

It only boosted his career

The British temperament finds good cheer

In a magnificent disappointment

Finally, in a change from the traditional mummers play role, Doctor Foster has to admit defeat, and he can’t bring this hero back to life.

DOCTOR FOSTER

Here I stand, Old Doctor Foster

And I know what I can, and what I cannot do

This man has done more in his short life than I ever could

But even I know when a man’s life is through

Here lies a man who learned how to move mountains

And we must remember his story to tell

For his legacy’s still all around us – no doubting

The greatness of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

I imagined the first line of the last verse as a bookend to the line from Dr Seuss’s final book; Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

“Kid, you’ll move mountains!

Today is your day!

Your mountain is waiting.

So get on your way!”

And we finish with a reminder that we are all just storytellers, telling the tale of a hero, bold, as Old Father Thames said in his introduction. The Doctor’s last line is only the second time that Brunel’s full name is used in the whole play, after the title character introduces himself at the start.

But in the end, in our play, Brunel Lives! He leaps to his feet without any Tip-Tap or Hocum Pocum and leads a final heroic Morris Dance as the crew of the SS Great Eastern finally set sail for South Australia.

And so the play arrived through a series of serendipitous coincidences, of story and history, time and place, form and structure, rhyme and rhythm. In its own way it became a success, from the original performances of Nine Lives in 2009, nine years ago today; three days later to mark the 150th anniversary of the death of Brunel, and through several revivals. There are a number of relevant performance locations linked to the stories we tell and we have taken our play to all the most resonant sites in Bristol. There are also an ongoing sequence of significant anniversaries of events in IKB’s life and career. This summer we performed the play during Bristol Harbour Festival on stage in Brunel Square, next to the SS Great Britain, two days after the 175th anniversary of the launching of this great ship.

The writing of it only deepened my respect and enthusiasm for the great man. But it has left me with something of a problem. I had hoped that I would develop a series of mummers play biographies, but the truth is that there isn’t anyone else quite like Isambard Kingdom Brunel. In the nine years since I still haven’t found any other life story more worthy of re-imagining as a mummers play.

After writing this play, I started more properly investigating the form and structure of traditional mummers plays on websites such as Master Mummers, an excellent research resource which include a wealth of information and links to hundreds of traditional scripts. The other plays we’ve done have tended to be more closely aligned with the source material, respecting it to a greater or lesser extent as required.

Going forward, it must be time to start thinking of writing another play, on a completely different topic, perhaps one that has fewer ties to the mumming play format and yet allows more freedom to create original rhymes and characters and stories. Perhaps I’ll write it, or perhaps you will. I look forward to reading it or seeing it or being in it. Mummers plays are a living tradition. Just give us room to rhyme!

En Avant!

With thanks to Greg Brownderville, Director of Creative Writing and Associate Professor of English at Southern Methodist University, who kindly asked me to speak with his students this evening over the interweb about the writing of mummers plays. Good luck to his students, and anyone else, who might be inspired to write one!

I read most of the above post by way of an introduction.

Photograph of Brunel By Robert Howlett (British, 1831–1858) (Metropolitan Museum of Art) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photographs of the 2018 cast taken by Patrick Slade.

All extracts of the script copyright © Gavin Skinner.

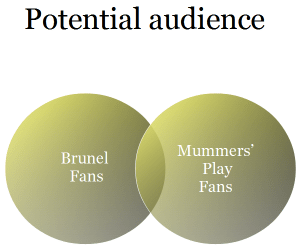

What I wanted to do was to create a kind of performance that drew from the mummers’ play tradition, and was also a play about Brunel. So to visualise the relationship between these sets of ideas, I drew this venn diagram. What we ended up with was a hybrid of two plays – a mummers play biography – and finding out where and how these two parts intersected was the challenge of writing the script.

What I wanted to do was to create a kind of performance that drew from the mummers’ play tradition, and was also a play about Brunel. So to visualise the relationship between these sets of ideas, I drew this venn diagram. What we ended up with was a hybrid of two plays – a mummers play biography – and finding out where and how these two parts intersected was the challenge of writing the script. Turning this around, it was also apparent that this play could potentially attract two audiences; an audience of Brunel fans, and audience of Mummers’ Play fans.

Turning this around, it was also apparent that this play could potentially attract two audiences; an audience of Brunel fans, and audience of Mummers’ Play fans.